* * *

Summary

Communication is always key for effective monetary policy-making, and the benefits of good communication are greatly increased in difficult times, says ECB Board member Peter Praet. Speaking at a conference of ECB watchers at Frankfurt he emphasises that central banks have been communicating more intensely during the crisis and by steering expectation more firmly their communication have had a stabilising effect. “We communicate what we are trying to achieve, and how we go about achieving it”, Mr Praet says. Notably, forward guidance has emerged as a useful complement to existing tools, he adds.

The introduction of Outright Monetary Transactions is according to Mr Praet an example of how communication added to the effectiveness of monetary policy tools. The ECB reaffirmed its commitment to the price stability mandate, as the pricing-in of unwarranted denomination scenarios could be a potential serious obstacle to fulfilling the mandate. He adds, “The OMT communication – unusual as it was in substance, for the ECB and probably for the entire community of central banks – was in fact strictly coherent with our general communication approach. It was a well-articulated frame of reference for our actions.”

Until now the ECB has resisted publishing accounts of the Governing Council meetings, Mr Praet states. One reason was according to him, that offering even more information on the ECB’s policy deliberations, in addition to what was already being provided, would come at the expense of clarity. On the other hand, publishing an account of the policy deliberations has now become “best practice” in the central banking community. Moreover, circumstances have changed, economic uncertainty has increased and the tools used now include non-standard measures. He highlighted: “It is important for us to provide the public with a fuller picture of the internal debate: we need to explain ourselves better.” To avoid a “cacophony problem”, with many voices tending to obscure the message, Mr Praet says he would favour to convey the content of the debate and the balance of views of Governing Council members.

Mr Praet concludes by explaining that the value of clarity in central bank communication is particularly evident in a financial crisis. He emphasises, “But communication – no matter how clear – only works if the communicator is credible. The ECB has a track record of following up words with deeds, and we intend to maintain it.”

* * *

Ladies and Gentlemen [1],

The last ‘’ECB and its Watchers’’ conference took place in June 2012. On that occasion I talked about heterogeneity across euro area countries, which was indeed a burning issue at that time, when fractures were running along national borders within the euro area and the integrity of the euro area itself was threatened. Today, almost two years on, the situation has improved distinctly. Markets are slowly but consistently re-integrating. Production and incomes are growing again and growth is spreading visibly to the most stressed parts of our Union. And our Union has expanded in the meantime, a sign that the euro project remains an anchor for the future of many Europeans once on the outskirts of the Continent.

But the necessary institutional transition – which is re-shaping and reinforcing the architecture of monetary union – is still proceeding. The central bank has been accomplishing its objective in a weak institutional environment, which did not facilitate its task. The monetary union is composed of 18 independent states, with important internal imbalances and with different historical backgrounds which shape their diverse policy priorities. For some, a central bank managing the aftermath of the great contraction is doing too little. For other, we are too bold and experimental. Our policy aim is clearly price stability for the euro area as a whole. Several times over the past years we have been confronted with economic and financial developments that had the potential, if not addressed forcefully, to compromise price stability for the euro area as a whole. We had to act, to take decisions, and to communicate these decisions to the public in a clear and coherent manner. In doing so we were not alone, as several central banks have used communication more intensively as an instrument of crisis control.

Monetary policy communication is never easy: one has to find the right vocabulary to communicate to a wide audience notions and content that are not immediately intuitive but highly relevant for the lives of many people. Monetary policy communication to a community of peoples as diverse as the euro area’s is even more challenging. This will be the subject of my thoughts today.

Put “central bank communication” into a search engine, you get millions of results; clearly, there is a lot of communication about how central bankers communicate these days. For good reason.

Communication is always key for effective monetary policy-making. This is true in normal times, but the benefits of good communication are greatly increased in difficult times. And yet, we should also be aware of the limits of communication. It is no substitute for action. In this, as in many other things, central banks are no different to anybody else: if warranted by the circumstances, they need to follow up words with actions, thereby validating earlier communication. Ultimately, this is the only way to maintain the credibility we need to achieve our price stability mandate.

The role of central bank communication

Let me start with the role of central bank communication in general.

Successful monetary policy is not only about controlling a very short-term interest rate but also – some would even say first and foremost – about affecting expectations of how those rates will evolve. [2] Those expectations matter because they influence the maturity spectrum of interest rates and, through that channel, the investment and saving decisions which determine economic growth. Therefore, by influencing expectations of future short-term interest rates, a central bank can ensure that its monetary policy decisions are well transmitted along the yield curve and to the broader economy [3].

How do central banks steer expectations in practice? Essentially with two key elements: one is clarity about their objective and the other is clarity about their monetary policy strategy to achieve that objective. These two elements help to create a certain degree of transparency about the central bank’s reaction function. This transparency can be further enhanced if the central bank lays out openly its assessment of the likely future evolution of the economy and the risks surrounding it. Based on these ingredients the public should under normal circumstances be able to develop over time a relatively good sense of how the central bank will react in a given circumstance. As a result, monetary policy becomes more predictable. This feeds into expectations about future policy rates, thereby strengthening the effectiveness of monetary policy. Notice that the communication of a clear inflation objective – defined in numerical terms – is a critical part of this mutual understanding between the central bank and its public, because it provides an anchor for inflation expectations. The importance of a credible inflation anchor cannot be emphasised enough: it contributes to stabilising inflation dynamics and it thereby helps the central bank to achieve its inflation objective.

In normal times, by explaining their current decisions, central banks provide sufficient information for the public to anticipate their future decisions, taking into account the economic outlook and its likely impact on the policy orientation. But in a financial crisis, this may not be enough. Especially when entering uncharted policy territory – for example, around the interest rate lower bound – it may be more difficult for the public to anticipate with any precision future economic conditions. Also, in a financial crisis, arbitrage in financial markets – a key mechanism that ensures a swift transmission of policy decisions throughout the inter-temporal chain of market prices – is impaired. Market participants need capital in order to be able to take positions that aid intertemporal transmission. But capital is scarce in times of financial stress.

Dispersion of expectations concerning the state of the economy and the degraded efficiency of the financial industry make the formation of longer-term interest rates an uncertain and noisy process in crises. This puts a premium on clear communication regarding the policy orientation. And in fact, during the crisis, central banks have been communicating more intensively and, in some cases, have expanded their communication toolkit. Notably, forward guidance has emerged as a useful complement to existing tools and several of the world’s major central banks have adopted it. This guidance consists of conditional communication on the future path of policy instruments, in most cases policy rates. In times of crisis, such guidance can help to eliminate one potential factor contributing to the overall environment of heightened uncertainty. Moreover, it allows an alignment of the public’s policy expectations with the central bank’s policy intentions.

Moving from theory to practice: Has central bank communication been an effective tool to strengthen monetary policy during the crisis? A preliminary assessment suggests that enhanced communication has generally served central banks well in dealing with exceptional developments, including policy rates approaching the lower bound [4]. By steering expectations more firmly, central banks’ communication initiatives have had a stabilising effect, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy. But to be effective, communication has to be followed by actual decisions, if and when the circumstances require them. Actions consistent with communication are only possible if the latter is in turn consistent with the ultimate objective and strategy of the central bank. Otherwise, the central bank either risks not following up on the communication or, if it does follow up, it runs the risk of not meeting its objective. In either case, hard-won credibility may be lost. This can be avoided by steering clear of making unconditional commitments about future policy action, but by always emphasising the conditional nature of any guidance. These conditions should be derived in a consistent manner from the central bank’s mandate and strategy.

The ECB’s approach to communication

Let me now turn to the ECB’s approach to communication.

Our approach starts from the premise that the central bank doesn’t have superior knowledge about how the world works. Nor are we likely to have better forecasting abilities than the majority of observers. So what we can do is to provide an explicit, well-articulated frame of reference for our actions. This is provided by the Governing Council’s quantitative definition of price stability, together with our stability-oriented monetary policy strategy – in short: we communicate what we are trying to achieve, and how we go about achieving it. In practical terms, this means that communication revolves around providing a narrative about the economy and the outlook for price stability relative to our objective. The ECB has established various channels through which this communication effectively reaches the whole of the euro area. These channels include the President’s press conferences, speeches by members of the Governing Council and the different official publications, which are translated into the official languages of the European Union. These were our main communication channels before the crisis, and they continued to play an important role during the crisis.

However, like other central banks, we have seen that in turbulent times it was useful to strengthen our communication. In particular, clarity of communication has been essential.

It’s not to say that clarity suddenly became a new principle of communication during the crisis. From the very beginning, we have insisted on improving the clarity – as opposed to the mere quantity – of our communication. [5] But the recent experience has shown that what constitutes clarity under normal circumstances may not be enough in more uncertain times. Let me highlight three instances where we found it useful to go beyond the standard clarity of our communication in order to achieve our price stability objective.

The first time, in the summer of 2012, we were faced with a severe tail risk that did not just pose downside risks to price stability, but actually threatened the very integrity of the euro area. Financial markets were rife with talk about the so-called “redenomination risk”. Spreads in some stressed jurisdictions increased to levels that were difficult to justify by the underlying fundamentals. As a result, there were clear risks to the singleness of the monetary policy of the ECB, aggravating an already impaired transmission mechanism. In response, we used our communication to “draw a line in the sand”: we had to clarify that we would do “whatever it takes” to deliver on our price stability mandate. This was followed up with further decisions and communication on how concretely, in our view, the necessary “whatever” could materialise at that particular juncture: the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme. What did we do? Effectively, we reaffirmed our full commitment to our price stability mandate. In addition, we said that we considered the pricing-in of unwarranted denomination scenarios as a potential serious obstacle to fulfilling our mandate and that we would therefore take appropriate action.

The OMT communication – unusual as it was in substance, for the ECB and probably for the entire community of central banks – was in fact strictly coherent with our general communication approach. It was a well-articulated frame of reference for our actions. And it was conditional. Two elements stand out. First, the policy was specifically directed at pricing out that particular financial premium which was compensating for risks of a break-up of monetary union. The “whatever it takes” had its limits in this specific objective of the policy initiative. Second, conditionality was intentionally an integral part of the design of the programme. Any intervention by central banks which have been assigned a price stability mandate has to take place in an environment where the solvency of counterparts is ensured. When we lend to banks, the supervisory solvency framework applies to our counterparties. With OMTs, this solvency framework would not have applied, because the issuer of the securities is sovereign. So, making OMT interventions conditional on a supranational surveillance framework that can monitor and safeguard the solvency of sovereigns – if and when this cannot be taken for granted – was a precondition for our action.

OMTs have been effective in restoring market functioning and confidence in the integrity of the euro area. In the period following the OMT announcement, tensions in sovereign bond markets subsided, supported also by policies at the national level.

Before OMT there was a high dispersion in the response of lending rates to reduction in the MRO rate. In some cases lending rates actually increased following cuts in the MRO. After OMT, the pass through has been more homogenous across countries and lending rates actually decreased. The response to the November cut may suggest more uniform pass-through. Overall there is evidence that OMT has favoured a reduction in financial fragmentation over time.

A second instance that helps to illustrate the importance of enhanced communication was in the context of our fixed rate full allotment procedure. In May 2013 we announced that we would extend the minimum horizon for this procedure until July 2014; in November 2013, this was further extended for as long as necessary, and at least until July 2015. This form of forward reassurance provided banks with some certainty about their Eurosystem funding for as long as necessary, and therefore especially in conditions of renewed turbulence. This reassurance has also helped ease concerns about the expiration of the two three-year operations.

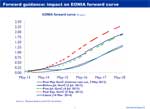

A third occasion when communication mattered was during last summer, when we were facing pronounced volatility in the money market forward curve which threatened to undermine our accommodative monetary policy stance. We succeeded in narrowing down market expectations regarding the path of our instruments. In other words, we clarified our reaction function by including forward guidance in our communication.

More precisely, on 4 July 2013 the Governing Council stated that it expected “the key ECB interest rates to remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time”. This qualitative statement about the likely evolution of policy interest rates was complemented by a narrative describing the macroeconomic conditions on which this guidance was based and which would effectively determine the length of the “extended period”. More precisely, the Governing Council explained that its expectation was based on “the overall subdued outlook for inflation extending into the medium term, given the broad-based weakness of the economy and subdued monetary dynamics”. This conditionality of the guidance ensures full consistency with the ECB’s strategy and mandate and thus ultimately guarantees its credibility.

Note a difference between our approach to verbal communication regarding the conditional path of our instrument and the approach taken by other central banks. Our main motivation was to regain control of the short-term segment of the money market in conditions in which that market was being influenced by expectations and external factors that we considered misaligned with our monetary policy inclinations. In other words, the stance of policy was considered appropriate, given the outlook for price stability prevailing at the time. But the way the stance was reflected in market prices had become subject to shocks that we wanted to minimise. Unlike other central banks, we had not reached the lower bound and the intention was not to inject further doses of monetary stimulus. We wanted to prevent the stimulus that had been introduced from being removed by excess market price volatility.

But that was not all: let me stress that we have followed up words with actions. In line with the Governing Council’s forward guidance, in particular its easing bias, we cut interest rates in November 2013 when risks to price stability materialised. In addition, last week we confirmed and – at the same time – updated our formulation in view of the evolving outlook for price stability. While staff forecasts gave us indications that we are gradually moving closer to 2% inflation over the medium term, we wanted to reassert our assessment that upside pressures to inflation will continue to be dampened by a large amount of economic slack, and by a weakened capacity of banks to create liquidity and credit for the economy. Because of the significant amount of unutilised capacity, our monetary policy stance will remain as it is – with interest rates staying at the present or lower levels – even as we see improvements in the economy. Once more, forward guidance has been the vehicle for a more precise articulation of the Governing Council’s thinking regarding the economy and the risks that surround our objective going forward. Once more, we followed up on the pledge we have consistently made in the past eight months since forward guidance was offered for the first time: we will keep updating our perception of the economic horizon, and will keep the public informed about our intentions, conditional on that outlook.

Let me illustrate how the ECB’s forward guidance has helped us to regain tighter control over market conditions and align them better with our own assessment.

First, starting from the low level reached after the May 2013 rate cut, the money market curve shifted upward following the tapering discussions. After the announcement of forward guidance on 4 July 2013 the money market curve flattened and shifted down, with forward rates declining by around five basis points at maturities beyond six months. In the months thereafter, the curve steepened and reached a new high in September 2013, before flattening again, in particular as a consequence of the November rate cut, which has effectively strengthened our forward guidance by following up on our communication when it was warranted by circumstances. More recently, the forward curve has overall remained close to the level reached after the May 2013 interest rate decision for maturities of up to two years..

Second, there was a lasting decline in market uncertainty about the path of future short-term interest rates. Implied densities extracted from EURIBOR options and used to gauge expectations of the forward OIS rate show that the dispersion of short-term rate expectations has declined from the elevated levels observed at the end of June 2013 to a level closer to that observed in early May 2013, after the interest rate cut. Third, since the announcement of forward guidance the sensitivity of money market forward rates to macroeconomic data releases has declined from the high levels reached in June 2013 and become more consistent with historical averages.

Overall, this evidence suggests that forward guidance has helped to provide greater clarity and transparency on the monetary policy orientation, conditional on the outlook for price stability.

Now, you may ask, what do OMTs, forward guidance and other instruments have in common? One thing, essentially: they can only work if we are credible.

And they have served us well – thanks to the clarity of our communication, but also to the credibility we have established over the years. In a way, our communication during the crisis can be seen as a promise to deliver on our mandate, no matter what.

But what I said so far does not mean our communication framework is perfect – there is always room for improvement. So looking ahead, we should ask ourselves: how we can improve our communication?

Publication of policy deliberations

As you know, at the ECB we have been discussing publishing some kind of record or “accounts” of our Governing Council meetings. What, and how much, of our policy deliberations should we publish? These questions are very much part of this old debate about our communication I mentioned before. So I think this is a good time to give you an update of our thinking on this issue.

It is true that until now we have resisted publishing such accounts. One reason was that we felt that offering even more information on our policy deliberations, in addition to what was already being provided, for example, by the President’s press conferences, would come at the expense of clarity. In technical jargon, it would diminish, rather than increase, the “signal-to-noise ratio”. A second reason was that we were a very young institution and still had to establish a track record of delivering on our mandate. So we were concerned that our policy debates could be misunderstood in ways that might damage our credibility.

So why have we changed our mind? It is true that other central banks’ experience with publishing minutes has generally been positive. In fact, publishing an account of the policy deliberations has now become “best practice” in the central banking community.

Moreover, circumstances have changed. Economic uncertainty has increased. So, too, has our toolbox, which now also includes various non-standard measures – which we are ready to use to achieve our price stability mandate. Non-standard measures are complex and so are the policy considerations that feed into the decisions on whether or not to adopt them. Therefore, providing more information on these considerations through published accounts adds complexity to the message. But this complexity is not “noise” but “signal”, as it reflects changed underlying realities. In a situation of fragmentation where non-standard measures play an important role, the analysis and considerations leading to policy decisions are by necessity much more complex than in normal times. Furthermore, by their very nature, unconventional measures can be, I don’t hesitate to admit, controversial – both inside and outside our institution. So it is important for us to provide the public with a fuller picture of the internal debate: we need to explain ourselves better.

Ultimately, we strive to be accountable because, in the words of Otmar Issing, this “reflects the conviction that in democratic society accountability is the ‘reverse side’ of central bank independence”. [6] Having established our credibility over the years, we now have the self-confidence to make another step that will enhance our institution’s transparency even further.

Having agreed that there is a case for the publication of accounts, we then need to ask: what should these accounts of our policy deliberations actually contain? What’s more, we need to strike a balance between the amount of information that we disclose, and the effectiveness of our message. How do we strike that balance?

Again, we should be guided by our principle of clarity. We want to avoid creating what Alan Blinder calls a “cacophony problem”, with many voices tending to obscure the message, rather than elucidating it. [7] I would favour to convey the content of the debate and the balance of views of Governing Council members.

Another important aspect to consider when framing our communication is the implications of the specific euro area context. It consists of different countries and nationalities, so it is not like the United States, the United Kingdom or Japan. We are a monetary union with 18 countries. It is crucial that the governors continue to act in a personal capacity and remain independent in their decision-making.

To sum up, the value of clarity in central bank communication is particularly evident in a financial crisis. But communication – no matter how clear – only works if the communicator is credible. The ECB has a track record of following up words with deeds, and we intend to maintain it.

What will remain of the communication initiatives taken during the crisis? Will they be part of our future communication toolkit? Perhaps forward guidance in this exact form will not be part of our toolkit as the type of communication we have adopted in normal times should be sufficiently clear. In contrast, any steps taken regarding the publication of accounts might well be viewed as being a permanent change to our communication framework. By providing additional clarity on our reaction function, this publication could help make our communication strategy more robust. The information provided will be adjusted to the information needs of the public over time, as the nature and complexity of the Governing Council deliberations reflect changing circumstances. Thus, with published accounts there may be less need for forward guidance in the future.

Thank you for your attention.

-

[1]I would like to thank Arthur Saint-Guilhem and Spyros Andreopoulos for their contribution in the preparation of this speech.

-

[2]On the role of expectations for monetary policy, see Woodford, M., Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy, Princeton University Press, 2003. For evidence on the role of the future path of policy, see Gürkaynak, R.S., Sack, B. and Swanson, E., “Do Actions Speak Louder Than Words? The Response of Asset Prices to Monetary Policy Actions and Statements”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 1(1), May 2005, pp. 52-93.

-

[3]On the importance of communication for monetary policy, see Woodford, M., “Central Bank Communication and Policy Effectiveness”, paper presented at the FRB Kansas City Symposium on “The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Future”, August 2005. See also Issing, O., “Communication, Transparency, Accountability: Monetary Policy in the Twenty-First Century”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Vol. 87 (2, part 1), 2005, pp. 65-83.

-

[4]See, for example, Gilchrist S., Lopez-Salido, D. and Zakrajsek, E., “Monetary Policy and Real Borrowing Costs at the Zero Lower Bound”, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Vol. 3, Federal Reserve Board, 2014. See also Femia, K., Friedman, S. and Sack, B., “The Effects of Policy Guidance on Perceptions of the Fed’s Reaction Function”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report, No. 652, 2013. See also Campbell, J.R., Evans, C.L., Fisher, J.D.M. and Justiniano, A., “Macroeconomic Effects of Federal Reserve Forward Guidance”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, spring 2012.

-

[5]I am referring here to the Buiter-Issing debate. See Buiter, W. (1999), “Alice in Euroland”, CEPR Policy Paper No. 1; and Issing, O. (1999), “The Eurosystem: Transparent and Accountable or ‘Willem in Euroland’.” CEPR Policy Paper No. 2.

-

[6]Op. cit., p. 7.

-

[7]Blinder, Alan S. (2004): “The Quiet Revolution: Central Banking Goes Modern.” Yale University Press.